The author of this blog post is Juan Vilata, a fisheries biologist with an MSc in Marine and Fisheries Science from the University of Aberdeen (UK), and over 12 years experience working in fisheries. Juan works as a consultant specialised in the analysis of fisheries data, and has extensive knowledge of IUU fishing and sustainability concerns, as well as broad experience as an observer in Atlantic and Indian Ocean fisheries. He has served as an observer on board of tuna purse seiners, pelagic trawlers, and long liners.

Juan makes his first contribution to the IUU fishing blog with a poignant post about the plight of fisheries observers in light of the recent, tragic and unexplained disappearances of four colleagues. His post highlights the risks observers face in the conduct of their work, and the responsibility that the tuna industry, and we all in the sector, owe to ensuring their safety.

DYING IN A LAWLESS SEA

By Juan Vilata

Since late 2017 and early 2018, a few online journals, newspapers and community radios mostly based in Pacific ocean nations have echoed a terrible fact: The “disappearance at sea” -death- of several fisheries observers from Papua New Guinea, whilst working onboard tuna fishing vessels over the last few years [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. The available information is scant and somewhat uncertain, and thus the exact number of disappearances is as of yet unclear. But there are at least four confirmed cases. Regardless of what the total number might be once confirmed, any death of a fisheries observer is an extremely worrying event, and more so if the circumstances of the disappearance/death are left unexplained. Sure enough, some of these cases could actually had been accidents (and there seems to be partial evidence that it might have been so in one case); after all, fishing is certainly a very dangerous activity, even in the absence of criminal circumstances. But all four?

On board and at sea, by Juan Vilata

It is important to be aware of the crucial role undertaken by fisheries observers: at the very minimum, their presence onboard a fishing vessel is aimed to check whether the fishery is conducted within the legal framework. But also, most fisheries’ claims to sustainability would be impossible (or at least very hard) to prove, if the vessels weren’t carrying observers onboard. By the very nature of their task, observers are always at risk of being deemed intruders by the crew. More so if that crew is used to engage in illegal fishing activities, of which there can be many modalities: for instance, they could be using banned gear, targeting moratoria species, exceeding their allotted quota, fishing in waters where they don’t have license to, finning sharks, or illegally transhipping their catch. The level and intensity of occurrence of these and many other kinds of illegal fishing activities is very variable amongst the different fleets; they can range from being very rare events, up to basically daily routine. And there’s also a wide array of fishing regulations which need to be monitored, such for instance, limits to the capture of vulnerable species, or measures and technical implements aiming to reduce discards. Depending on how strict the regulatory framework is (regulations are not always compulsory), their breach might be deemed illegal or else it might be still legal but clearly unsustainable. Regardless of these distinctions, an unmonitored fishing vessel is much more likely to engage into these practices than another one which carries an observer onboard.

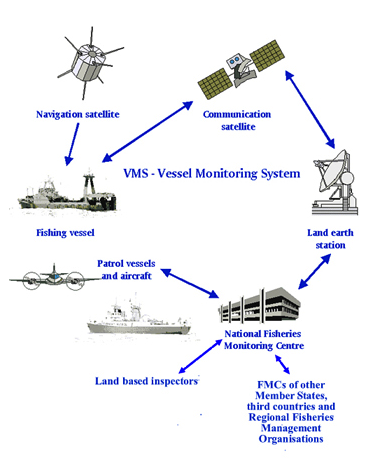

So, in short, although there are other means to monitor the activity of a fishing vessel (for instance, satellite monitoring systems, which are being continuously improved), the first and foremost check of the activities of the vessel is up to the observer. Depending on the specification of the observer program, if the observers witness some serious infringement, they might be required to report it by radio, or at least write it down in their reports. And the crew knows this. It is certainly not a comfortable situation. Depending on the seriousness of the circumstances -including the gravity of the infringement, the value of the catch, the vessel’s legal story, and other variables- observers might be subjected to anything ranging from the offering of bribes to serious threats, in order to prevent them from reporting what they observed.

Now, one obvious question about the missing PNG observers could be “How can this happen?” How can (at least) four people vanish into thin air after boarding their assigned vessels? Well, it does happen because tuna fisheries are a multi-billion industry [8], hence there’s a lot of money at stake, and because out there in the sea, onboard the distant water fishing fleets, there’s in practice a legal void [9, 10, 11, 12]. As things are now, in all likelihood, anything that happens onboard a distant fishing vessel will be left unpunished. Most nations owning large distant water fleets deny against all logic that they have any responsibility for what happens in their vessels. And yet, it stands to reason: similarly to diplomatic outposts, any vessel sailing under the flag of a given country should be considered an extension of such country. And therefore, the flag country should be accountable for whatever happens onboard. This issue of the current impunity of flag countries has been reviewed by multiple sources, one of which is the excellent short documentary by the NGO Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) about human rights abuses at the Taiwanese distant waters fishing fleet [13].

But let’s not forget about the missing observers. They boarded the vessels, alive, never to return. It’s not as if they were anonymous: they had names, faces, and families. And it is registered which vessel was boarded by each one of them, and on which day. The names of the vessels are likely to have been changed by now, in an attempt by the vessel owners to escape prosecution from the authorities. However, the vessels always belong to a fishing and/or seafood trading company, and this can be traced, even though they’re almost always screened behind ghost companies based in convenience countries. Unmasking the real identity of the company owning a given vessel can in fact be a detective’s job. But it can be done.

Since no one else seems to care or do much about their safety, fisheries observers have organized themselves within APO -the international Association for Professional Observers-, and are running a project called OSIRS: the registry of all Observer Casualties, Injuries, and Near Misses [14]. OSIRS tries to keep track of every incident affecting the safety of fisheries observers, regardless of their nationality or the flags of the vessels they boarded. APO is a non-for-profit association with limited means; nevertheless, they’re doing a remarkable effort by keeping track of all these incidents. Given the secrecy around most of them, this is no easy task.

On board transhipping vessels, by Juan Vilata

But now a second obvious question would be: “What is being done about it?” Well, not much, apparently. At the national level, PNG authorities do not seem to be making very strong advances in tracing the companies and identifying the people responsible. Whether this is for lack of funding, insufficiently prepared staff, or any other reason, the investigation does not bode well. Let’s not forget though that PNG is one of the world’s poorest nations [15], and its political stability is very fragile [16, 17, 18], all of which might undermine its capacities to take this investigation through to the end. But this shouldn’t be taken exclusively as an internal PNG’s issue: the vessels from which the observers disappeared belong to foreign fleets, and they caught tuna that by now has likely entered the global supply chain, and thus might have arrived to our plates.

And here’s the point: “What are the international tuna market actors doing about this?” Let’s imagine for a moment that the nationality of the observers had been different: Can anyone imagine four Australians (or French, or Americans, or Spaniards, or British, or Norwegians) working as fisheries observers, going missing onboard tuna fishing vessels (at least three of them in as of yet completely unexplained circumstances), and that nothing was done about it? Where are the international mass media, why aren’t they denouncing this?

These disappearances cannot, and must not, be left unresolved. This is a question of responsibility to the victims’ families, but also to ourselves: if we acquiesce with this impunity, we’ll be sharing the responsibility, as long as we keep consuming tuna whilst asking no questions. And more crucially, by doing nothing about it, we’re practically guarantying that this will happen yet again.

References

[1] Papua New Guinea Post Courier (2018). Increased Deaths of PNG observers. https://bit.ly/2IMhV9b

[2] RNZ (2017). PNG seeks to investigate purse seiner after observer’s death. https://bit.ly/2GkM1BX

[3] RNZ (2018). PNG parliament told about fisheries observers who disappear. https://bit.ly/2CHNcpn

[4] Keith Jackson – ASOPA (2018). On the trail of the missing PNG fisheries observers. https://bit.ly/2GkgTCJ

[5] www.wikitribune.com (2017). Updated: Murder and abuse – the price of your sashimi. https://bit.ly/2pDfX22

[6] The National (2018). Safety of fisheries observers a priority. https://bit.ly/2pAfIWg

[7] Human rights at sea.org (2017). Investigative report and case study: Fisheries abuses and related deaths at sea in the Pacific region. HRAS Report 1 December 2017. https://bit.ly/2G5YxC7

[8] Galland, G., Rogers, A., & Nickson, A. (2016).The Pew Charitable Trusts. Netting Billions: A Global Valuation of Tuna. https://bit.ly/1W1T97C

[9] Urbina, I. (2015). Sea Slaves: The Human Misery That Feeds Pets and Livestock. The New York Times, 07.27.2015. https://bit.ly/2ulHTx3

[10] Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), (2010). All at Sea: The Abuse of Human Rights Aboard Illegal Fishing Vessels. EJF, London (2010). https://bit.ly/2pGBeb9

[11] Marschke, M., & Vandergeest, P. (2016). Slavery scandals: Unpacking labour challenges and policy responses within the off-shore fisheries sector. Marine Policy, 68, 39-46. https://bit.ly/2pFdyUx

[12] Rosello, M. (2016). Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing Control in the Exclusive Economic Zone: a Brief Appraisal of Regulatory Deficits and Accountability Strategies. Croatian International Relations Review, 22(75), 39-68. https://bit.ly/2pJtmXl

[13] Environmental Justice Foundation. Exploitation and lawlessness: the dark side of Taiwan’s fishing fleet. https://bit.ly/2GkDWxe

[14] APO/OSIRS. http://www.apo-observers.org/misses

[15] UNDP (2018). About Papua New Guinea. https://bit.ly/2DT0Czy

[16] May, R. (2013). State and society in Papua New Guinea: the first twenty-five years. ANU Press. https://bit.ly/2pEMeqp

[17] Allen, M. G. (2013). Melanesia’s violent environments: Towards a political ecology of conflict in the western Pacific. Geoforum, 44, 152-161.

[18] May, R. J. (2017). Papua New Guinea Under the O’Neill Government: Has There Been a Shift in Political Style? SSGM discussion paper 2017/6. State, Society and Governance in Melanesia. The Australian National University. https://bit.ly/2ISjAK8

You must be logged in to post a comment.